His Equipment

Maximilian J. St. George’s book, Traveling Light… contains a list of the author’s kit. Bearing in mind the title he gave to his book, you might have already guessed that it wasn’t a long one. He says the following:

“My equipment was as light as possible, for one pound more or less makes a great difference in a long trip. All my impedimenta [equipment] was carried in a canvas knapsack, eighteen inches long, eight inches deep and two inches wide, strapped to the handlebars of the bicycle. Behind me on a carrier , I had a blanket to sleep on, and a small rubberized cape, bought in London as protection against rain. In the knapsack were a pair of light trousers, some handkerchiefs, several pairs of socks, a small folding mirror, and a comb, a razor, a shaving stick and a strop [a strip of leather for sharpening razors], note books, lead pencil, repair cement, a roll of rubber and a few pieces of outer tire. I wore a strong suit of clothes and shoes, a weather-proof cap, a celluloid collar, a light blue shirt and light-weight underclothing.

This was all I had. It may seem too little, especially on a trip of sixteen months, and yet it proved adequate for all occasions. It is more practical and much easier to replace a worn article of wearing apparel by buying a new one than than to carry extra luggage for months. A little water and soap will make a celluloid collar look like new, and when other laundry work became necessary I did it in the evening before retiring, and started out the following morning with a clean supply. while riding through the day, I never wore my coat. By folding, wrapping and tying to the handlebars it was kept clean, and on arriving at a city or town where I meant to remain for some time, my coat and the extra trousers came into service. This with light luggage, and a lighter heart, I toured Europe.”

Maximilian J. St. George, Traveling Light or Cycling Europe on Fifty Cents a Day

His Bicycle

He doesn’t tell us a great deal about the bicycle. Or rather bicycles. He refers frequently to his ‘wheel’ when actually he is referring to the whole bike and this can be a little confusing for the modern-day reader. His first bike is a mystery to say the least. Upon arriving in Poitiers, France, he says the following:

“As the pedals of my bicycle had been a little out of plumb for some time, I went to a bicycle mechanic in Poitiers to locate the trouble. I had to take out the pedals for him, as he did not know how. The right one proved to be broken in the hub. In order to remove the sleeve, he placed an iron bar against the hub cover and began to hammer away despite my warning that he would break the mechanism. After a lot of pounding, out came the hub, the cover smashed to bits and the crank sleeve broken.

“Now you have done it!” I cried in dismay. “Can you repair the damage?”

In the most nonchalant manner he responded: “No, nor can anyone in all of France. That’s what you get for having an American wheel [bicycle].”

“Then you must pay for the damage you have caused.”

He only stuck out his lower lip, looked foolish and smiled a long surprised “no.”“

Maximilian J. St. George, Traveling Light or Cycling Europe on Fifty Cents a Day

After trying to go down the legal route (he is a lawyer) by visiting various local big wigs, he returns to the mechanic:

“That individual seemed to have grown more solicitous for my welfare. He promised to keep my wheel [bicycle] until the broken parts could arrive from America and then ship the repaired wheel [bicycle] wherever I would direct. As he was under no obligation to me, this appeared to be the best plan to follow.”

Maximilian J. St. George, Traveling Light or Cycling Europe on Fifty Cents a Day

Max then continues his journey by train to Bordeaux where he works for a period of time in a factory. The factory owner arranges for the bike to be brought to Bordeaux and writes to Max to inform his that the parts have arrived from America. However, all the required parts do not make it as far as Bordeaux and Max suspects that the mechanic in Poitiers has kept hold of them for “revenge“. By this point Max is in Pau and has become friendly with an American – a wealthy brewer from Indiana – who he happened to have met at the basilica in Lourdes. This chap goes by the name of ‘H—— B——‘ in the book and then simply ‘Mr B——‘. (Max does this throughout the book, only identifying his acquaintances using the initials.) It turns out that meeting Mr B—— was a good move:

“When Mr. B—— saw the letter he at once advised me to go ahead and buy another wheel [bicycle]. That afternoon, as we were sitting in the park enjoying the delightful air, he handed me one hundred dollars….

Two days later, mounted on an “Alcyon,” which cost fifty-five dollars, I set out for Biarritz and Spain.”

Maximilian J. St. George, Traveling Light or Cycling Europe on Fifty Cents a Day

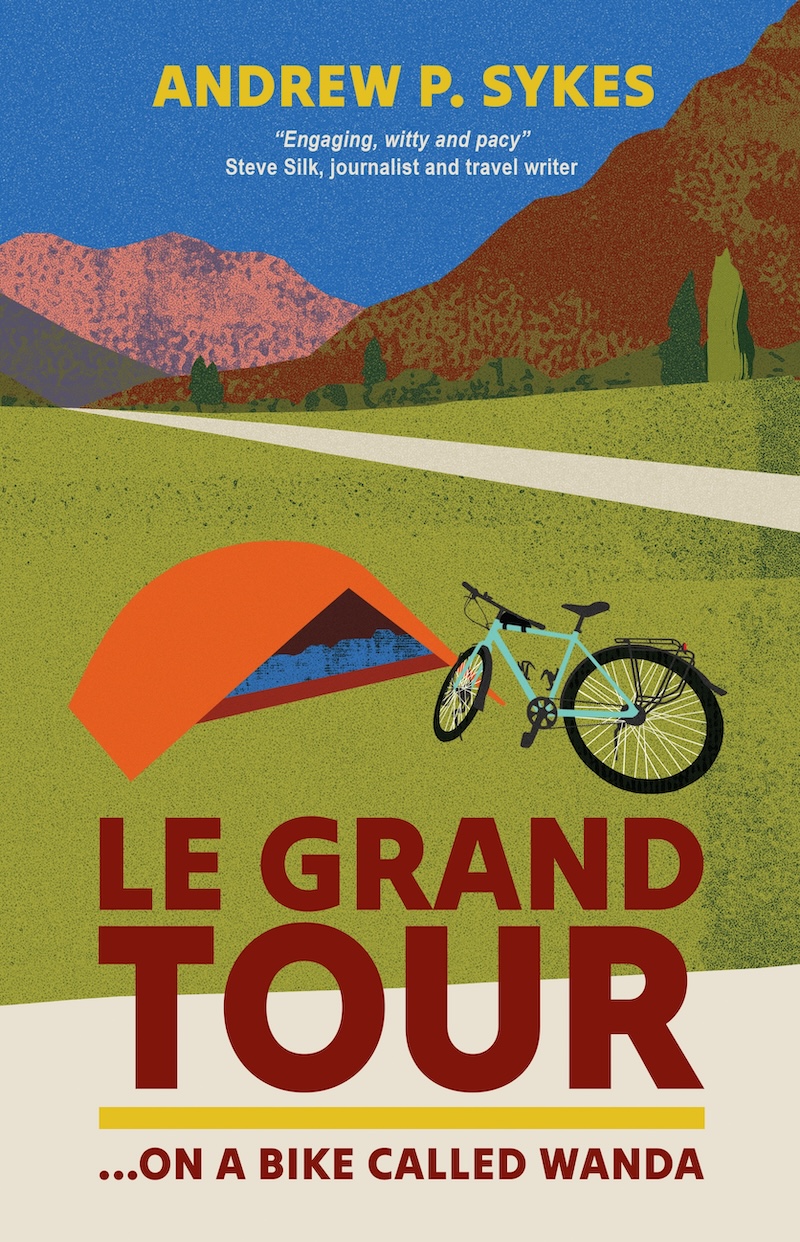

And here he is with his new bicycle, the Alcyon:

According to Wikipdeia…

“Alcyon originated from about 1890 when Edmond Gentil started the manufacture of bicycles in Neuilly, Seine. In 1902, this was complemented by motorcycle production and in 1906, the first cars were shown at the fair “Mondial de l’Automobile” in Paris, France. Also in 1906 it founded the professional Alcyon cycling team which was active until 1955, including winning the Tour de France 6 times.”

Wikipedia

There are some good pictures of what Max’s new bike might have looked like on the sterba-bike.cz website which showcases an Alcyon bike from 1920 (although there are some clear differences between the bike shown there and his bike as shown above).